- Our Services

- Financial Planning

- Wealth Creation

- Superannuation

- Retirement Financial Advisers in Adelaide

- Insurance Financial Planner Adelaide

- Estate Planning

- Debt & Mortgage Advice

- Debt Management & Budgeting

- Financial Advice for Aged Care Adelaide

- Redundancy Planning

- Centrelink & Government Benefits

- Maximising Your Finances In Your 20s And 30s

- About Us

- FAQs

- Resources

- In the News

- Careers With Us

- Contact

- Signup

- Self-Managed Super Funds

Labor returned to Government in Australia – key challenges and risks

Labor returned to Government in Australia – key challenges and risks

Key points

– The return of Labor with an increased majority basically means more of the same in terms of key economic policies.

– The key challenges for the Government are to boost productivity and hence living standards, improve housing supply and affordability, get the budget under better control and strengthen the economy in the face of the challenges to global trade posed by Trump.

– It’s possible the ALP could use its enhanced political capital to push a market friendly reform agenda or push down a less market friendly path under influence from the Senate Greens. The former would probably require a crisis though and the latter would likely be seen as too politically risky.

– The impact on investment markets is likely to be minor.

Labor returned

Despite the “cost of living crisis”, Labor has been returned with a landslide victory and the biggest seat differential versus the opposition since 1977. Coming into this year with polling showing the Coalition moving ahead, this did not look likely at all. Then along came President Trump and his mayhem leading to a swing back to centrist incumbents – first in Canada and now in Australia. Of course, there is a lot more to it with Labor running a far better campaign with more coherent and less risky policies amidst a lack of clarity as to what the Coalition stood for, leading to many deciding to stick with what they knew. This note looks at the implications for investment markets and the key challenges facing the Government.

No big policy changes based on election promises

Labor’s key economic policies are well known.

- It’s committed to allowing most first home buyers to get in with just a 5% deposit and its Help to Buy Scheme is about to start up. It’s also ramping up its supply side efforts with a fund to build 100,000 homes for first home buyers on top of the Housing Australia Fund helping to build 30,000 affordable homes and its overall goal of building 1.2 million homes over five years. But its demand side policies are likely to dominate in the near term adding to home prices.

- Labor has already legislated for ongoing modest tax cuts and has promised a standard $1000 pa tax deduction. This will provide a modest boost to household incomes.

- Labor has continued the electricity rebates to December, with battery subsidies and a continuing push to renewables to supply 82% of electricity by 2030. This provides ongoing certainty for clean energy providers but with continued risks around the energy transition.

- It’s projecting a slowdown in net migration to 260,000 in 2025-26 and 225,000 pa thereafter which will take some pressure off housing, but avoid the threat to economic growth the LNP’s bigger cuts risked.

- Most of Labor’s policy measures were announced prior to or in the March Budget which saw a $35bn fiscal easing over five years. It claims the measures it announced since will be covered by further savings, from more cuts to consultants and increased student visa fees. So basically, the fiscal situation remains as in the Budget. In fact, budget data up to March suggests the 2024-25 deficit could actually end up being substantially smaller than the $28bn deficit forecast in the Budget, as the revenue windfall continues. But it’s still likely going to see a return to deficit and remain so over the decade ahead.

This is basically more of the same and as Labor’s return to government was flagged by recent opinion polls (albeit not the size of its win), the election outcome does not justify any significant move in shares, the $A or bond yields, with their near-term outlook dominated by Trump’s erratic trade policies. And with the budget and debt trajectories little different to that in the March Budget, there are no significant implications for the RBA, which we see cutting interest rates further starting later this month. Although, all the extra spending does mean that interest rates will likely be higher than might otherwise have been the case.

Elections, political parties and shares

That said, since the 1980s there has been a tendency for shares to rise after elections as uncertainty lifts. 10 out of the 15 elections since 1983 saw shares up 3 months later with an average 4.2% gain.

Australian shares before and after elections

| Election | Winner | Aust shares, % chg 8 weeks up to election | Aust shares. % chg 3 mths after election |

| Mar 1983 | ALP | -0.6 | 19.8 |

| Dec 1984 | ALP | 0.0 | 5.4 |

| Jul 1987 | ALP | 3.7 | 15.9 |

| Mar 1990 | ALP | -7.0 | -3.5 |

| Mar 1993 | ALP | 9.0 | 3.2 |

| Mar 1996 | Coalition | 2.3 | -2.0 |

| Oct 1998 | Coalition | -2.6 | 11.1 |

| Nov 2001 | Coalition | 5.9 | 5.4 |

| Oct 2004 | Coalition | 5.9 | 9.9 |

| Nov 2007 | ALP | -2.9 | -11.7 |

| Aug 2010 | ALP | 0.5 | 5.7 |

| Sep 2013 | Coalition | 4.6 | -1.0 |

| Jul 2016 | Coalition | -0.6 | 4.5 |

| May 2019 | Coalition | 2.9 | 0.4 |

| May 2022 | ALP | -5.1 | -0.4 |

| May 2025 | ALP | 3.4 | |

| Average (ex 2025) | 1.1 | 4.2 |

Based on All Ords price index. Source: Bloomberg, AMP

Once in government, political parties are usually forced to adopt at least half sensible policies if they wish to ensure rising living standards. Since WWII, Australian shares have performed better under Coalition Governments, although the Whitlam and Rudd/Gillard Governments had the misfortune of global bear markets and the reformist Hawke/Keating period saw the strongest returns of any post war government (a message to the Albanese Government!). See the next table.

Average share market returns of post war governments

| Period, All Ords Accumulation Index | Labor

Govts, %pa |

Coalition

Govts, %pa |

| 1945 – 1949 | 11.7 | |

| 1949 – 1972 | 13.2 | |

| 1972 – 1975 | -4.2 | |

| 1975 – 1983 | 14.8 | |

| 1983 – 1996 | 17.2 | |

| 1996 – 2007 | 14.1 | |

| 2007 – 2013 | -0.4 | |

| 2013 – 2022 | 9.1 | |

| 2022 – 2025 | 6.7 | |

| Weighted Average | 9.7 | 12.9 |

Source: ASX, Reuters, Bloomberg, AMP

Challenges for the continuing Labor government

The election campaigns from both major parties were a disappointment. All we got was band-aid solutions and a spendathon of promises starting in January, with little to boost living standards, get the budget back in balance and meet the fundamental challenges to global trade posed by Trump. The four key economic challenges for the Government are to:

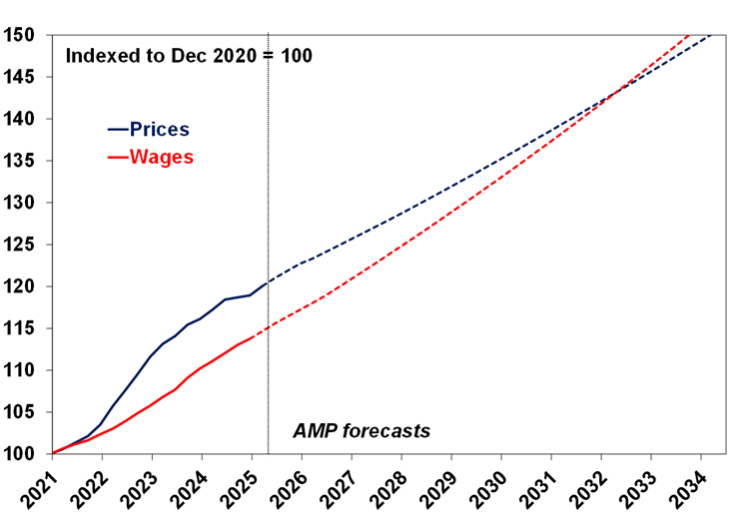

- Boost productivity to boost living standards – the “cost of living” was voters’ key concern. It’s reflected in a 10% fall in real household disposable income per person – which reflects wages (+15% since December 2020) not keeping up with prices (+20%) and a surge in tax and interest payments – and a broader stagnation in real incomes over the last decade. Real wages are now rising again but at the current rate won’t catch up to their December 2020 level until around 2032.

Australia Inflation vs Wages

Source: ABS, AMP

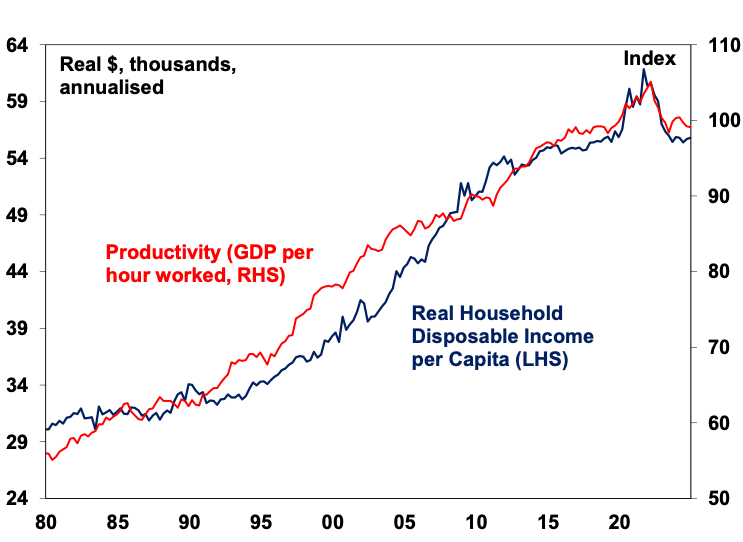

The key is to boost productivity (ie output per hour worked), as it is the main driver of real wages and real incomes. As can be seen in the next chart both have stagnated over the last decade.

Australians’ Living Standards

Source: ABS, AMP

Just boosting wages growth without boosting productivity will mean higher inflation & a wage price spiral leaving no one better off. Boosting productivity requires a combination of: tax reform (to reduce reliance on income tax, raise the GST, limit the capital gains tax discount and switch from stamp duty to land tax); labour and product market deregulation; competition reforms; improving education; reforming the health system with a greater focus on price signals and prevention; limiting public spending as it’s crowding out private activity, etc The good news is that the Treasurer recognises the need to boost productivity and has an agenda around human capital, competition, technology, energy and the care economy. But he needs to go further.

- Improve housing affordability – it’s been deteriorating for decades, impacting productivity & equity. But the focus has to be on boosting supply. The Trumpets were right on one thing – we need to make it easier for people to live in regional centres & commute to big cities.

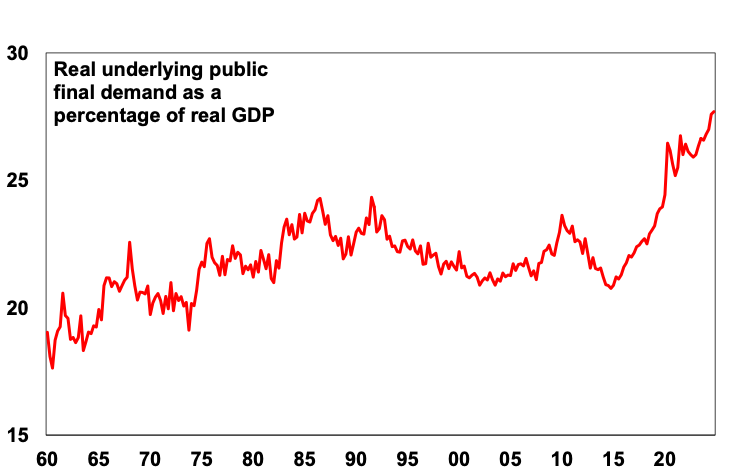

- Get the budget under control – the Government has been lucky with a $350bn revenue windfall on the back of a strong jobs market and high commodity prices. But an increasing proportion of this is translating into record public spending leading to higher than otherwise inflation and interest rates. Structural spending pressures around the NDIS, health, aged care, defence and public debt interest are now taking the budget back into deficit when public debt is already high. They need to be checked and offset by savings.

Australian losing its AAA credit rating is unlikely as deficit and debt projections look little different from those in the March Budget. But it is a risk particularly if the revenue windfall reverses. The increasing use of “off-budget” funds which add to debt is also making a mockery of budget transparency. A good place to start would be a new version of Hawke and Keating’s budget restraint “trilogy” which focussed on capping public spending and tax as a share of GDP and a commitment to cut the budget deficit and at the same time review the Charter of Budget Honesty to constrain off-budget funds.

Public sending as a share of Australian GDP

Source: ABS, AMP

- Put the economy on a strong footing to survive Trump – his hit to trade with a flow on to our exports reinforces the need to make the economy stronger. Which takes us back to boosting productivity.

Opportunities and risks

A reasonable interpretation of the election result is that it was a vote for centrist stability with the election providing no mandate for radical reforms. An optimistic take though is that the Government could use its enhanced political capital to push more aggressively down a productivity reform agenda, e.g. in terms of tax reform and deregulation possibly with the help of the Coalition. However, this would probably require a shock to push the Government into action like a sharp fall in commodity prices cutting national income, reversing the budget revenue windfall and leading to a credit rating downgrade. This is partly what motivated Hawke and Keating in the 1980s. On the other hand, there is also a risk the Government could push down a less market friendly path under influence from the Greens in the Senate – focussing narrowly on things like reining in access to property tax concessions. But this would likely be seen by the PM as too risky politically.

Dr Shane Oliver – Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP

Important note: While every care has been taken in the preparation of this document, neither National Mutual Funds Management Ltd (ABN 32 006 787 720, AFSL 234652) (NMFM), AMP Limited ABN 49 079 354 519 nor any other member of the AMP Group (AMP) makes any representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This document has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this document, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This document is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided. This document is not intended for distribution or use in any jurisdiction where it would be contrary to applicable laws, regulations or directives and does not constitute a recommendation, offer, solicitation or invitation to invest.